Coming into the 2000 presidential election, a casual observer could feel pretty confident about two things. First, that Florida would likely be close. And, second, that this uncertainty would not spill across the state’s northern border, given that Georgia was certain to vote for George W. Bush by a healthy margin. As, in fact, it did, matching other Deep South states.

What a difference 22 years makes. Both states have since evolved significantly. Florida backed Donald Trump by a healthy margin in 2020 and reelected Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) by a gigantic one last month. But in Georgia, Republicans faltered. Gov. Brian Kemp (R) was reelected easily — thanks in part to his standing athwart Trump’s politics. In the Senate contests held over the past two years in the state, though, Democrats went 3 for 3. And, of course, it also went into Biden’s win column in 2020.

“Swing state” is always a vague identifier, one better applied after the fact. But despite the success of Republicans at the state level (even further down from Kemp), it is clearly the case that Georgia no longer qualifies as a red state.

Consider the shifts the state has seen internally since 2000. Over the past 20 years, rural areas of the state have moved to the right, mirroring rural counties nationally. But the big counties — the ones near Atlanta and other large suburban counties — have moved hard to the left. You can see that below; counties to the left of the diagonal line shifted to the Democrats from 2000 to 2020.

About 7.7 million people live in counties that shifted to the Democrats since 2000. Only about 3.1 million live in counties that shifted to the GOP.

A lot of that is centered near Atlanta, in the northwestern part of the state. It and its suburbs are clearly visible on the map below, showing county vote results, with circles sized to represent how many votes were cast in each county in the indicated election. Look at the 2000 presidential map … and then jump down to the 2020 one. That cluster in the northeast went from largely red to heavily blue.

It’s important to recognize the differences between those last two maps. It shows how each county voted in November’s gubernatorial contest and in this week’s Senate runoff. Notice that the map at right is a bit more heavily blue. That string of three smaller counties at center-right, for example — Baldwin, Washington and Jefferson counties, for those familiar — is light-red in the Kemp race and light-blue in the Senate contest.

That’s important context for considering how counties have evolved. Below, we track the vote margin and the percentage of the statewide vote from each county since 2000. At the top, you can see that Fulton County has moved to the left — but in 2022, its gubernatorial result was more red than its 2020 presidential vote. It’s Senate-runoff vote, though, was bluer.

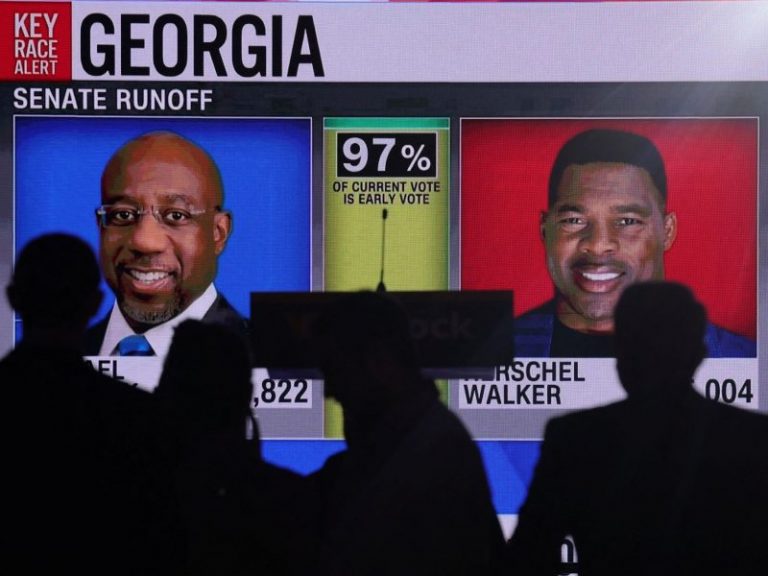

That pattern holds in other counties, too. It’s probably a reflection in part of Kemp’s palatability to Democrats after his post-2020 battles with Trump — and with the deep flaws of Republican Senate candidate Herschel Walker.

One more way to look at the shift is to simply look at the composition of the state. The most obvious shift from 2000 to 2020 was the flip of Gwinnett and Cobb counties from heavily red to heavily blue. In the gubernatorial race, Cobb was lighter blue than it had been in November 2020, one reason Kemp was able to win so easily. But the overall shift is obvious: The state is not as red as it used to be.

The “why” of all this is a different, more complicated question. It certainly involves demography and population growth. But, then, Florida is diverse and has seen population growth of its own. It’s complex — more complex than is worth getting into here.

Instead, we’ll just draw a simple conclusion from the data above. Georgia is no longer a red state. It is, like many others, a purple state — though, given the partisan bifurcation along urban-rural lines, it’s probably better described as a blue-red state.

That, too, is a more complicated discussion for another time.