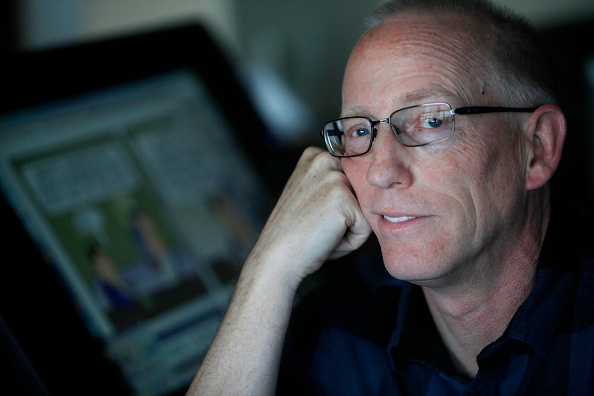

For months it has seemed inevitable that the “Dilbert” comic strip’s run as a popular American newspaper cartoon would end precisely as it did: a victim of controversy triggered by its creator, Scott Adams. In retrospect, even the specific catalyst seems as if it could have been predicted. Adams’s increasing espousal of right-wing racial politics — and his embrace of the or-am-I-just-joking mode of online boundary-pushing — led him to declare in a video last week that he viewed Black Americans as a “hate group.”

“If nearly half of all Blacks are not okay with White people … that’s a hate group,” Adams said, citing polling from Rasmussen Reports. “I don’t want to have anything to do with them. And I would say, based on the current way things are going, the best advice I would give to White people is to get the hell away from Black people … because there is no fixing this.”

And that was that. Syndicators of “Dilbert” dropped the strip, as did individual newspapers. The cartoon will no longer appear in The Washington Post, among other news outlets. The damage was done.

Adams himself has at times predicted his own “cancellation,” his ostracization for making controversial or repugnant claims. This is itself a common tactic on the right, people amplifying their supposed anti-left credentials by suggesting their views are unacceptably politically incorrect. Often, the controversy fails to materialize or, at least, to reach the scale that Adams achieved over the past week. But it’s the thought that counts.

Tracking Adams’s evolution alongside the online right is fascinating. He supported Donald Trump’s efforts to goad the left, if not every aspect of his presidency. In the past few years, his politics have been more Tucker-Carlson-ish, rejecting government and other institutions as hobbled, moronic or nefarious. Adams enjoys presenting himself as smarter and more clever than everyone else, leading him to couch controversial statements with belated winks in the manner of Twitter owner Elon Musk (who rushed to support Adams in the wake of the new controversy).

What makes the situation with Adams interesting, though, isn’t that it’s unique. Quite the opposite. He (like Trump and Musk) has been able to tread further into controversy thanks to celebrity and power. Years of pushing boundaries only to see them stretch to accommodate him (as with the introduction of the first Black Dilbert character last year — who, true to Adams’s worldview, identified as White) simply reinforced his own self-confidence and led him to push harder.

There are rewards for this on the right. Donald Trump Jr. has gone from minding a real estate empire to creating a lib-baiting one. You can get attention and praise and go viral online with successfully structured efforts to make Democrats mad. By offering evidence that the political right is correct and the political left toxic and deluded, you can generate attention capital, one of the most important currencies in right-wing politics.

Which brings us to Rasmussen Reports.

Like Adams, Rasmussen has spent the post-Trump years fervently engaged in culture-war fights. The company, once generally considered conservative but still primarily a polling firm, has shifted its focus. Its online presence includes the results of its Republican-friendly polls, but also amplifies right-wing causes and rhetoric. In the wake of the 2020 election, it shared misinformation about fraud and backed Trump’s efforts to reject electors. In recent months, it has boosted anti-vaccination conspiracy theories. Its polls, meanwhile, are often sponsored by hard-right organizations and causes.

So, earlier this month, it embraced a different aspect of right-wing politics: the idea that White people face discrimination and racism equal to or greater than Black or other non-White groups.

This has been a central motivator on the right for well over a decade. Trump’s election in 2016 was powered in no small degree by Republican primary voters concerned about the status of White Americans. This sense was heightened by the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement and the immigration surge that occurred in 2014. The idea was clearly a central part of opposition to the presidency of Barack Obama as well, both because he was not White and because his election overlapped with increased concern about the perceived demographic decline of Whites. Polling has shown that Republicans consistently express the belief that White Americans are as likely to face discrimination as other racial groups, if not more.

Rasmussen, looking to leverage that idea, published the results of a poll on Twitter.

As summarized, it suggests that only 53 percent of Black Americans agree that “it’s okay to be White.” Hence Adams’s framing: “nearly half of all Blacks are not okay with White people.”

By itself, though, this is wrong. Only 26 percent say that they “disagree,” according to the tweet. But remember that these figures are for only a small number of Black poll respondents. If Rasmussen’s 1,000-person poll included 136 Black adults (matching the national population) the margin of error here would likely be about 8 percentage points. (This isn’t really how polling works, but Rasmussen’s methodology is dubious enough anyway that we’ll just use it as our example.)

More importantly, though, Rasmussen didn’t ask if people thought it was okay to be White. They asked if people agreed with the statement, “It’s okay to be White.”

Why is this important? Consider another, even more loaded question: Do you agree with the statement “all lives matter’? No one cognizant of American politics in the last decade would not recognize that statement for what it is. It’s not a comment about whether lives matter; it’s a rebuttal to the activist phrase “Black lives matter.” It’s not about all lives, it’s about the Black Lives Matter movement.

“It’s okay to be White” involves a similarly loaded, if less broadly recognized, context. After the phrase first emerged from 4chan, a site on which trolling is celebrated, Carlson defended it, characteristically suggesting that the racial division was being fomented by those who understood the troll as a troll.

“It’s a sort of rhetorical judo flip that works by willfully misinterpreting critiques of structural white supremacy or racism as an attack on the mere fact of being caucasian,” writer Julian Sanchez observed on Twitter. “And then stage 2 of the judo flip — which is the real point of the whole maneuver — is that when someone who understands what’s going on takes exception, the troll gets to gasp in horror to anyone who doesn’t get what’s up ‘Oh, so you think it’s NOT OK to be white?’ ”

Not everyone would immediately recognize the ploy here, including, presumably, many Black respondents who took the question at face value. Many, it is safe to assume, spotted it immediately. Rasmussen certainly should have, given that they were asking about it. Rasmussen should also, therefore, recognize that its presentation of the question and the responses strains a generous assumption of good faith.

Adams, like many on the right, was happy to seize upon this “data point” as validating his assumptions about race in general and Black people specifically. You don’t simply jump from one poll about the views of Black Americans to a position of “I endorse avoiding Black people at all cost.” This is a position that is already in your immediate vicinity if all it takes to be nudged across the boundary is one misleading poll question from a partisan pollster.

That Adams was in that vicinity was obvious from his various past comments. That Musk quickly rose to his defense, casting the media as racist, was predictable: He’s mired in the same politics and the same approach to politics as Adams.

The result is a trap that many others, particularly on the right, have fallen into over the past decade. Immersed in an echo chamber where Whites are the victims, they make public assertions that reflect that position. And when the inevitable happens, when the assertions trigger a backlash, the echo chamber only grows louder: Here’s another White man, punished for his views.

Outside of the echo chamber, the view is different. The guy from Dilbert, huh? Sounds about right.