WILMINGTON, Del. — When Delaware’s acting U.S. attorney David C. Weiss celebrated a fraud conviction in 2010, he was joined by a key partner in the case: Beau Biden, the state’s attorney general.

Weiss worked with Joe Biden’s eldest son to hash out prosecution strategies. “We will continue to aggressively pursue all types of fraud in order to protect the public,” Weiss said in his part of a statement with Beau Biden on the fraud case.

Today, that little-known history highlights the deep challenges Weiss faces as he pursues a newly recharged investigation into Beau’s brother, Hunter Biden, in a small state long politically dominated by their father.

Although Democrats point to Weiss’s appointment by President Donald Trump as evidence of his independence, the full story of his career is more nuanced, as he spent two years as acting U.S. attorney under President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden and then remained as a top deputy for the remainder of their term.

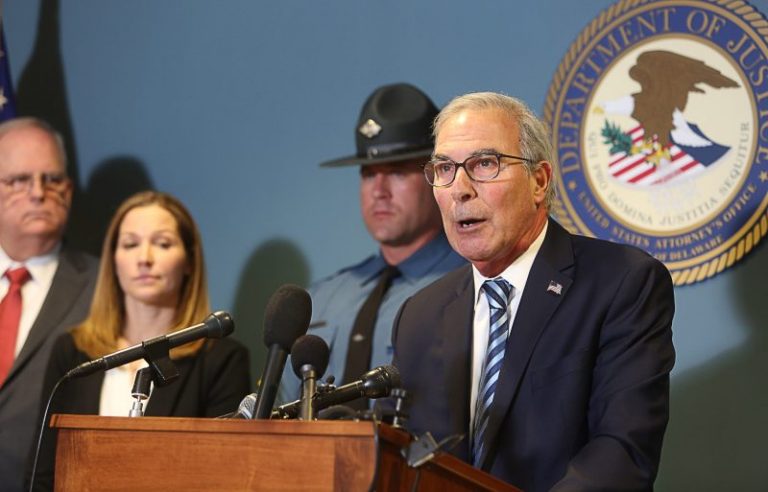

Weiss, who was named special counsel on Aug. 11, is now confronting blowback from formerly supportive Republicans, who accuse him of offering Hunter Biden an unfairly soft plea deal on tax and gun charges. Sen. Lindsey O. Graham (R-S.C.) summarized that view when he said on Fox News that “Mr. Weiss has been compromised.” A spokesman for House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jim Jordan (R-Ohio) said Weiss “can’t be trusted.” Whistleblowers interviewed by the GOP have also accused Weiss and the Justice Department of limiting the scope of the Hunter Biden probe, a claim Weiss has denied.

But Biden’s allies questioned why the plea deal dramatically fell apart in court amid claims from Hunter Biden’s lawyers that they’d been misled about the terms. His lawyers in an Aug. 13 filing slammed what it called the government’s decision to “renege on the previously agreed-upon Plea Agreement.”

Weiss declined to comment. The White House also declined to comment, noting that Weiss is conducting an independent investigation. Hunter Biden’s attorneys did not respond to requests for comment.

Attorney General Merrick Garland said Aug. 11 at the Justice Department, “I am confident that Mr. Weiss will carry out his responsibility in an evenhanded and urgent manner and in accordance with the highest traditions of this department.”

The tensions are heightened by a fact that locals say is inevitable in a place like Delaware: Weiss’s career has often brought him into contact with Biden, his family and his political allies in the state.

“The state is a small town and everybody knows each other,” said Henry Klingeman, who previously defended a client in a case prosecuted by Weiss. In Delaware, Biden “has been the most consequential figure since 1972 and I’m sure he and Weiss crossed paths.”

As the 67-year-old Weiss faces the harshest spotlight of his career, the criticisms confound some of those who know him here as an apolitical, follow-the-facts, registered-Republican prosecutor who has a reputation for being an honest broker when asked to investigate the state’s most powerful Democrats.

Weiss has for decades been involved in high-profile cases in Delaware. He has prosecuted lawmakers, including allies of the Biden family; played a key role in a murder case involving a prominent Democrat; and won convictions in a major bank fraud only to have them overturned.

Now these cases provide a prelude to the biggest one of his career, the five-year investigation and possible trial of the president’s son Hunter amid a 2024 reelection campaign.

“What it tells you is that David is going to follow the facts, and he is not going to be dissuaded by the fact that an institution or an individual is high-profile and ‘powerful,’” said Thomas Ostrander, an attorney who worked with Weiss at a law firm.

Weiss’s first experience as a special prosecutor came in 1989 in a politically charged Delaware case centered on a Democratic lawmaker.

Weiss had graduated from Widener University’s Delaware Law School and, after he failed in an effort to be hired by a leading law firm, served as a federal prosecutor. After three years in that job, he was appointed as special prosecutor in the high-profile case.

Weiss examined allegations that a Democratic member of the New Castle County Council in Wilmington had extorted $100,000 in exchange for his vote. The councilman, Ronald Aiello, pleaded guilty, giving Weiss one of his first major prosecutorial victories.

For 25 years, Aiello has not publicly discussed the case. Reached by The Washington Post last week, Aiello said his experience suggested Hunter Biden should be prepared for an aggressive investigation.

“I’d be scared to death,” Aiello said, recounting how he said he had been treated “unfairly” by Weiss. Aiello said he served nearly four years in prison.

“Delaware is a corrupt state,” Aiello said. “The mistake I made in Delaware is I went to jail and I should have ratted on everybody,” he added. “And I kept my mouth shut.”

In the wake of convicting Aiello, Weiss reapplied to Duane Morris, one of the firms that had rejected him; this time he got the job. Weiss hung the rejection letter he’d received years before and signed by a firm member, Ostrander, on his office wall — which Ostrander discovered when greeting his new colleague.

Ostrander said he soon came to Weiss to ask that he represent the family of a woman who had gone missing in 1996 and, it was feared, had been murdered. Weiss agreed to advise the family as the criminal case unfolded in a federal courtroom in Delaware. As the case developed, it opened a window into the seamy upper echelons of Delaware politics, which Weiss navigated for years in the public spotlight.

The missing woman was Anne Marie Fahey, the 30-year-old scheduling secretary to Gov. Thomas R. Carper (D). The suspected killer was Thomas Joseph Capano, a Democrat who had been chief counsel to Gov. Michael N. Castle (R). Prosecutors alleged Capano had an affair with Fahey, killed her and dumped her body in the ocean.

In his role as the Fahey family attorney, Weiss acted as a liaison with federal authorities in the case and, as he later put it in a Senate questionnaire, served “to shadow the government’s investigation” and help the family “navigate the substantial media attention.”

As the sensational case attracted national attention, he challenged Capano “to come in and talk to the authorities,” and frequently appeared on the federal courthouse steps in Wilmington to talk to the press, according to “And Never Let Her Go,” a book on the case. Capano was convicted of first-degree murder in 1999.

“We could not have gotten through it without David’s leadership,” said Kathleen Fahey, Anne Marie’s sister.

Robert Fahey, Anne Marie’s brother who has remained close to Weiss, called him “apolitical” and said the Fahey case demonstrated his tenacity.

“He’ll follow the facts and he’ll follow the rules,” Robert Fahey said. “Not in a super aggressive way, but he’s like a dog with a bone. And he’ll keep at it until the facts are laid out and the right process is followed.”

In the wake of the conviction, Weiss and Ostrander sued the Capano family on behalf of the Faheys, resulting in a settlement that is confidential, Ostrander said.

“David is very adept at assessing a claim relative to what the facts are and how they’re going to play out and how they’re going to apply for the legal theory,” Ostrander said. “Follow the facts, develop the facts you can prove, and use those to develop the case.”

Weiss returned as a federal prosecutor in 2007, when U.S. Attorney Colm Connolly, who had prosecuted the case against Capano, hired him as first assistant U.S. attorney. Weiss became acting U.S. attorney when Connolly resigned following Obama and Biden’s 2008 election — a position he held for the next two years due to the administration’s delay in nominating a replacement.

“I can say I’m pleased I have had the chance to serve as long as I have,” Weiss told the News-Journal in a March 2010 story. Joe Biden and Weiss appeared together at least once during that time, at an Oct. 17, 2010, swearing-in of a federal judge in Wilmington.

As the top federal prosecutor in Wilmington, Weiss collaborated with his local equivalent: Beau Biden, who had been elected Delaware attorney general in 2006. Weiss and Beau Biden conducted joint investigations and determined which office had jurisdiction in various cases.

Tim Mullaney Sr., who served as Beau Biden’s chief of staff at the state attorney general’s office, said the office often worked with the U.S. attorney’s office during Weiss’s tenure. He didn’t believe Beau Biden and Weiss had a relationship outside of their work. “We are always working hand-in-glove with federal government; there’s nothing unusual about that.”

It also wouldn’t have been strange for Weiss to run into Joe Biden.

“Everybody knows everybody in Delaware, and it wasn’t unusual to see [Joe Biden] at the bookstore, the ice cream shop. It is normal,” Mullaney said.

When Connolly’s successor finally took office in December 2010, Weiss returned to his former position as first assistant U.S. attorney, a job that he held during the last six years of the Obama-Biden administration.

In his role as a top deputy, Weiss showed a willingness to go after major institutions in the state — and he also did not hesitate to go after figures tied to Biden.

In 2012, Weiss oversaw the prosecution of Christopher Tigani, a liquor industry executive, for illegal campaign contributions, some of which were steered to Joe Biden’s 2008 presidential campaign. Weiss took on the case because the U.S. attorney, Charles Oberly III, had close ties to both Joe and Beau Biden. Tigani pleaded guilty to federal election and tax charges and was sentenced to two years in prison. He could not be reached for comment.

In a presentencing memorandum submitted by Weiss, he provided a telling analysis of what is known as the “Delaware Way,” which Biden has described as a sense of community and bipartisanship. Weiss provided a darker interpretation, writing that Tigani had become the “embodiment of the ‘Delaware Way,’ a concept described uniformly by the defendant and others as a form of soft corruption, intersecting business and political interests, which has existed in this State for years.”

In some cases Weiss worked out plea deals that avoided jail time. In one case against a stent manufacturer who allegedly had lied to the Food and Drug Administration, but whose product was credited with saving lives, he crafted a guilty plea deal that included probation and fines, according to Connolly, the former U.S. attorney.

“No one went to jail, but justice, in my view, was done,” Connolly said at Weiss’s investiture ceremony, according to his remarks.

In his most prominent case, which began with indictments in 2015, Weiss eventually oversaw the prosecution of four top executives of Delaware’s most prominent financial firm, Wilmington Trust, on allegations they had hid the extent of bad loans from regulators.

Klingeman, a lawyer for one of the defendants, said that he spoke regularly with Weiss and tried to convince him that prosecution was unwarranted. But Weiss went ahead anyway.

“Fundamentally, I always thought they were wrong to prosecute the Wilmington Trust case,” Klingeman said in an interview. “But he was always willing to meet and to listen. … My experience with him was, you know, he was quite aggressive.”

When Weiss won convictions of the four bank officials in 2018 for bank fraud and conspiracy, he pushed back at critics of the case.

“Recently it’s become a bit of sport to ridicule the DOJ, the FBI and other federal agencies,” Weiss said, contending that the case showed his Delaware office could successfully take on powerful interests.

But that bravado crumbled when a federal appeals court struck down the verdict three years later, saying Weiss had produced insufficient evidence that the defendants ran the bank with the intent to commit fraud — an outcome that Klingeman said he had anticipated when he tried to dissuade Weiss from trying his client.

Weiss said at the time that the decision was “extremely disappointing,” while noting that the bank had made forfeitures to victims and that some defendants had pleaded guilty to fraud. He decided not to seek a retrial of the four executives, saying the court had limited his options and that he wanted to focus on other challenges such as the rise in violent crime.

Weiss began investigating Hunter Biden in 2018, shortly after Trump nominated him as U.S. attorney and he was confirmed by a Senate voice vote. In response to a written question from a Democratic senator during the nomination process, Weiss wrote, “No one, at any point during the process, has asked me to commit that I would be loyal to President Trump” or the attorney general.

Republicans had been calling for an investigation into whether Hunter Biden’s business work had enabled millions of dollars in international deals to be funneled to Joe Biden, a claim that the Bidens have denied and for which the GOP has not provided evidence. The case soon ballooned to include Hunter Biden’s unpaid taxes, drug use and other issues.

Under normal circumstances, President Biden would have replaced Weiss with a Democrat after his 2020 election. But that would have led to allegations of political interference in the investigation into Hunter Biden, so the president left Weiss in the job.

Republicans, meanwhile, began their own congressional investigation. That case has led to testimony from two IRS whistleblowers who accused the Department of Justice of stymieing the case, a claim echoed in part in an FBI agent’s recently released testimony. One IRS agent said Weiss told him and others in a meeting that he could not file certain charges outside of Delaware.

Weiss and the Justice Department said at the time that he had all the authority he needed to file charges.

In late July, the case appeared all but over, as Weiss authorized a deal in which Hunter Biden would plead guilty to two tax misdemeanors and enter a diversion program over a gun charge, probably enabling him to avoid jail time. That deal blew up after U.S. District Judge Maryellen Noreika questioned it, and the two sides disagreed over whether it protected Hunter Biden from possible future charges.

The failure to seal the deal angered Hunter Biden’s lawyers and also befuddled some Weiss allies who privately questioned how he could have let the matter go so far without certainty that the deal would be accepted by the court.

Garland said in his recent Justice Department appearance that Weiss’s investigation had reached a stage where he needed to name a special counsel. Garland said the move confirmed his commitment to provide Weiss with all the resources needed. Weiss said in an Aug. 11 filing that with the collapse of the plea deal, “a trial is therefore in order.”

Republicans for months had called for Weiss to be named a special counsel. More than 30 Senate Republicans in September sent a letter to Garland asking that Weiss “be extended special counsel protections and authorities.”

But many of those who signed the letter said they no longer have faith in Weiss. “Given the underhanded plea deal negotiated by the U.S. Attorney from President Biden’s home state, it’s clear Mr. Weiss isn’t the right person the job,” Sen. Charles E. Grassley (R-Iowa) said in an Aug. 11 statement.

The Bidens are now preparing for the possibility that Hunter Biden could be on trial during his father’s reelection campaign — potentially drawing new focus on the president’s actions.

Those who have observed Weiss for years say his professional intersections with the Biden family over the years will have no bearing on his work as special counsel. They insist he will follow the facts and tune out the partisan noise.

“He was appointed by Donald Trump, and now if he doesn’t do everything Republicans want, they denigrate him,” said Mullaney, the former chief of staff to Beau Biden. He said it was “inconceivable” Weiss would play favorites, saying, “Hopefully he is not paying attention to all the rhetoric.”

Alice Crites and Magda Jean-Louis contributed to this report.