Attorneys offered opening arguments in the criminal trial of Donald Trump on Monday in Manhattan, beginning the process of presenting to the jury the state’s case against the former president. The jury will ultimately be asked not whether Trump is guilty of a crime in the abstract but, instead, whether the state provided enough evidence to eliminate any doubt that he violated the letter of the law. This means that the letter of the specific law undergirding the charges in the indictment against Trump is crucially important.

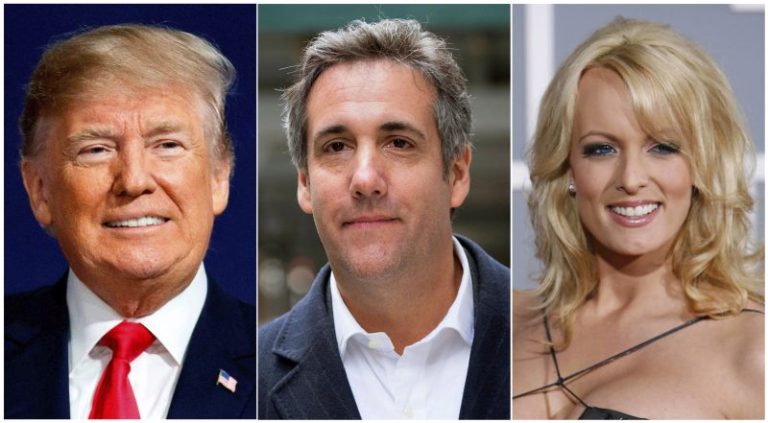

In that indictment, Trump is charged with 34 felonies, each predicated on his having allegedly falsified business records. Specifically, prosecutors argue, he caused the Trump Organization and his personal trust to record payments made to attorney Michael Cohen in 2017 as retainer fees rather than as reimbursements for the $130,000 that Cohen paid to adult-film actress Stormy Daniels before the 2016 presidential election.

Falsifying business records is not always a felony. But if the “intent to defraud includes an intent to commit another crime or to aid or conceal the commission thereof,” the New York criminal statute reads, it can be charged as one. As it was in each of the charges against Trump.

So what is the “another crime?” It isn’t articulated in the criminal indictment. Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg (D) was somewhat vague when the indictment was handed down, saying that the intent was “to conceal crimes that hid damaging information from the voting public during the 2016 presidential election.”

Offering his opening statement Monday, prosecutor Matthew Colangelo made clear that the crime was centered on Cohen’s payment to Daniels.

“This was a planned, coordinated, long-running conspiracy to influence the 2016 election,” Colangelo said, “to help Donald Trump get elected through illegal expenditures, to silence people who had something bad to say about his behavior, using doctored corporate records. It was election fraud, pure and simple.”

Trump’s attorney, Todd Blanche, rejected that idea.

“There’s nothing wrong with trying to influence an election; it’s called democracy,” he said during his opening statement. “They put something sinister on this idea as if it was a crime. You’ll learn it’s not.”

Except that it can be. And in this case, almost certainly is.

At issue is another fairly esoteric body of law: campaign-finance limits. These laws limit how much money people can contribute to political campaigns and how campaigns have to report what they take in and how they spend it. Outside parties can spend money on promoting candidates, too; those are called independent expenditures. But they can’t coordinate with the campaigns or candidates on how they plan to do so.

The goal of those laws — an important aspect of the issue at hand — is centrally to limit the corruption that could follow from a big donor bankrolling a candidate’s entire campaign. If, say, Google could simply put up a candidate and spend $1 billion getting her elected to the Senate, it would be hard for anyone to compete — and Google would have a presumably loyal senator sitting in D.C.

So with those prohibitions in mind, consider what Cohen did — as he admitted when pleading guilty to federal campaign-finance charges.

Cohen and a representative of Trump’s campaign (later revealed to be Trump) met with David Pecker — then chairman of American Media Inc. and publisher of the National Enquirer — in August 2015. Pecker offered to help the campaign by buying stories that would reflect negatively on Trump and then burying them. AMI and Pecker confirmed this story in a non-prosecution agreement reached with the government.

Already, you can see that this is an offer to benefit the campaign that involved coordination with agents of the campaign; that is, with people empowered to act on the campaign’s behalf. That’s Trump himself, of course, but also Cohen, who would represent the campaign publicly and discussed campaign strategy with Trump.

When Pecker later bought a similar story from former Playboy model Karen McDougal for $150,000 intending to bury it, it 1) was an action taken to benefit the campaign, as per the August 2015 meeting and 2) was not an independent expenditure, since the McDougal payment was made in consultation with Cohen. Cohen pleaded guilty to “causing an unlawful corporate contribution” — since corporations like AMI can’t legally contribute to campaigns, and the $150,000 was a non-monetary contribution to Trump. AMI and Pecker offered testimony, resulting in that non-prosecution agreement.

In October 2016, a month before the election, Pecker informed Cohen about Daniels’s story. Cohen reached a deal with Daniels’s attorney — also McDougal’s attorney — for $130,000, but didn’t pay immediately. Only when Cohen learned that Daniels was thinking of going public elsewhere in the days before the election did Cohen finally pay the money.

Cohen pleaded guilty to federal campaign-finance charges related to this as well. That plea didn’t depend on arguing that Cohen was an agent of the campaign, though; instead, it argued that Cohen made the contribution “in cooperation, consultation, and concert with, and at the request and suggestion of one or more members of the campaign.” A later filing identified that member of the campaign: Trump.

Some on the right have argued that the payment to Daniels didn’t violate campaign-finance law. Earlier this month, Trump shared on social media a 2023 article written by the National Review’s Andrew McCarthy, making that case.

The timing, McCarthy argued, “was just common-sense hardball” on the part of Daniels and McDougal, “striking when their leverage against the notoriously parsimonious Trump was at its height; it didn’t mean that [nondisclosure agreements] — which Trump had plenty of other personal, political, and business incentives to pay for — were necessarily in-kind campaign expenses.”

Perhaps this could be an argument made against such charges, albeit a dubious one. After all, Cohen recorded a September 2016 conversation with Trump in which they discussed the McDougal case and, in another context, the need to bury negative information until after Election Day. The idea that Trump and Cohen didn’t view the Daniels payment as related to the campaign is ridiculous — especially since it first came to their attention immediately after The Washington Post published the “Access Hollywood” tape, drawing new scrutiny to Trump’s interactions with women.

But Trump’s defense team isn’t trying to make McCarthy’s argument anyway.

“There’s nothing wrong with trying to influence an election,” Blanche told jurors Monday. “It’s called democracy.”

So if Trump was admittedly trying to influence the election by agreeing with Cohen to pay off Daniels, then Cohen — as he admitted in federal court — violated campaign-finance laws. And therefore, if the repayments to Cohen were falsified to obscure their intent — remember, the Cohen-Daniels story didn’t become public until 2018, after the reimbursements had been made — it seems as though that was done to “conceal the commission” of those campaign-finance violations.

Proving Trump actively caused the records to be falsified is the central job of Manhattan prosecutors. Demonstrating that the records were allegedly falsified to obscure this other crime seems a much easier task.