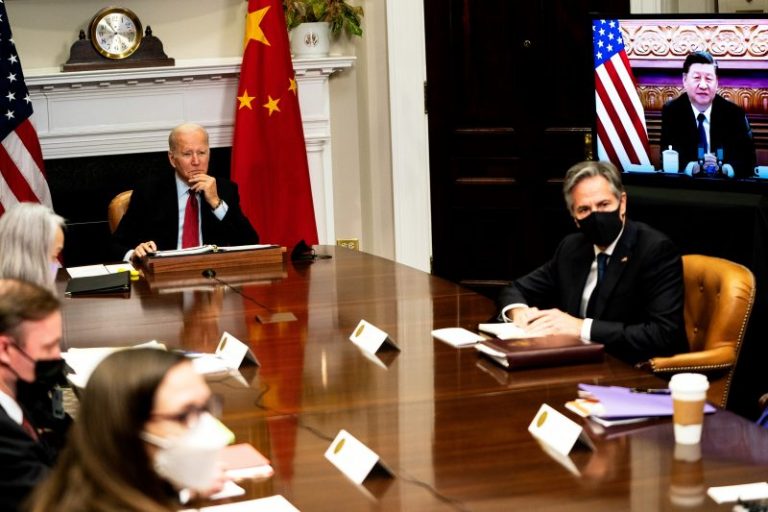

Minutes before President Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping entered an ornate ballroom at a palatial Bali hotel in November for their first face-to-face meeting as leaders of their countries, the two shared a warm handshake and expressed optimism that the meeting would help thaw a relationship that was at its lowest point in decades.

The two met for three hours and, although there was no major breakthrough, Biden said afterward that there “need not be a new Cold War” between the global superpowers. And he vowed that the United States and China would maintain open lines of communication, revealing that he had asked Secretary of State Antony Blinken to travel to Beijing to continue the conversation.

But Biden’s months-long effort to improve the U.S.-China relationship hit a major hurdle Friday when he chose to postpone Blinken’s trip to China just hours before his top diplomat was set to leave. The decision came in response to the Pentagon’s discovery of an alleged Chinese spy balloon flying over the continental United States.

For Biden, the episode was an important moment in what has been a years-long diplomatic dance with Xi, whom he got to know when the two were both vice presidents more than a decade ago. Despite the warmth displayed in Bali, experts and those close to the White House said Biden’s decision to send a clear message to China — and perhaps to Republican critics at home — reflected his long-held view that the biggest threat to the U.S.-China relationship is not a deliberate act of war, but a miscalculation or mistake that could escalate into a catastrophic conflict.

“Uppermost on President Biden’s mind when he thinks about China is the very real risk that he sees of an incident or accident that occurs because the Chinese have a misunderstanding about the situation and, in many cases, a misunderstanding about the United States,” said Daniel Russel, a U.S. diplomat who helped plan Biden’s trip to meet with Xi in 2011.

By deferring Blinken’s trip, Russel said, Biden is aiming to send China a clear signal. “He was determined to show the United States is not a declining power, that the United States is not economically on the ropes,” Russel said. “He’s determined to show the United States isn’t backing away from its values and commitment to support democracy and international law.”

The incident is also a sharp reminder that one of Biden’s top priorities since taking office has been shifting American foreign policy toward confronting China, which he views as the biggest long-term threat to American interests. That determination has been eclipsed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but it remains an underpinning of Biden’s worldview.

For their part, Republicans, who sometimes appear divided in their opposition to Russia, are more unified in opposing China — sometimes criticizing Biden for not being tough enough, other times working with him. One of the biggest bipartisan actions of Biden’s presidency has been passage of the Chips Act, a $52.7 billion investment in American semiconductor manufacturing intended in large part to ensure the U.S. does not fall behind China in that crucial industry.

Beijing on Friday acknowledged that the balloon had originated in China, but said it was a meteorological aircraft that was blown off course — claims that have been rejected by Pentagon officials, who say they are certain the balloon is a surveillance craft.

A U.S. military aircraft on Saturday downed the suspected surveillance balloon. Biden said he told the Pentagon on Wednesday to shoot down the balloon as soon as possible without putting anyone on the ground at risk.

Some White House allies said postponing Blinken’s trip was an overreaction to the incident, particularly because U.S. officials have said they do not think the balloon was able to gather information that cannot be acquired in other ways, such as spy satellites. The Chinese government acknowledged the balloon’s existence only after its location surfaced publicly, said one senior administration official, adding that Beijing had expressed regret.

“We note the PRC’s statement of regret. But the presence of this balloon in our airspace is a clear violation,” the person said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss private diplomatic communication. PRC refers to the People’s Republic of China.

Biden was briefed on the balloon this week and asked the military to present options. Senior military officers, including Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and Gen. Mark A. Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, strongly recommended against shooting down the balloon because of the risk it would pose to people on the ground, the senior administration official said, and Biden followed that recommendation. By Saturday, the balloon was just over the Atlantic coast and no longer posed a risk when officials decided to shoot it down.

One White House ally said they thought delaying the trip was a mistake and was largely a reaction to criticism from Republicans, who quickly tried to use the incident to paint Biden as soft on China, a charge the president has been sensitive to since the start of his presidency. Still, Republicans were divided on the wisdom of postponing Blinken’s trip.

Scott Anderson, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, said that after Biden and Xi met in Bali, there seemed to be a cooling between the two leaders and both appeared open to a more conciliatory tone. He added that the Biden administration could have used Blinken’s trip to confront China directly about the balloon.

“We’ve known the United States and China fly satellites over each other’s countries. … These provocations happen all the time and countries need to be held to account for them,” Anderson said. “But closing down a major avenue of high-level conversation at a moment when there’s heightened tension with China seems like a miscalculation and a missed opportunity.”

Biden officials were careful to stress that the decision was simply a postponement and not a cancellation of the trip. A State Department official said that Blinken informed China’s top foreign affairs official, Wang Yi, on Friday that he would plan to travel to China “at the earliest opportunity when conditions allow.” State Department officials declined to say when the time may be more ripe for a visit.

Biden, whose more than 50-year career in public service has often revolved around foreign policy, has pitched himself to voters as a statesman with decades of experience dealing with some of the world’s most difficult leaders, including Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin. In the 2020 campaign, he was at pains to create a contrast with President Donald Trump’s unorthodox and often chaotic approach to foreign policy.

Of Xi, Biden regularly boasts that the two have spent dozens of hours together over the years, recalling that when he was vice president, President Barack Obama dispatched him to get to know Xi, who was then China’s second-in-command.

“Back when Barack was president, we knew Xi Jinping was going to be president,” Biden recounted at a Democratic political event Friday night. “It wasn’t appropriate for a president to get to know and spend time with a vice president, so I did.”

Biden also repeated his claim that he and Xi traveled more than 17,000 miles together. And Biden often shares an anecdote about Xi in which the Chinese leader asked him to define America. “Possibilities,” Biden says he told Xi.

The question now may be whether the two leaders’ long relationship can help calm the current flare-up. Biden’s oft-shared facts and anecdotes belie a far more complicated and pressure-filled dynamic between them.

On the campaign trail, Biden called Xi a “thug,” though he also conceded he is a “smart guy.” He also said Xi does not have a democratic “bone in his body.”

And Biden’s relationship with Xi since assuming the presidency two years ago has been consumed by diplomatic skirmishes and brewing tensions over Taiwan.

Days before then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan in August, for instance, Xi asked Biden during a phone call to find a way to keep Pelosi from coming. Chinese officials also repeatedly warned their U.S. counterparts that there might be significant consequences from Pelosi’s visit to the self-governing island that Beijing considers part of its territory.

Biden was not able to halt Pelosi’s visit despite signals from his administration that it was not in favor of her trip, though Biden never made a direct request of her. After the visit, China responded by escalating actions in and around the Taiwan Strait, including firing missiles into the waters around Taiwan and conducting military drills that crossed the median line of the Taiwan Strait.

Biden has also antagonized top Chinese officials by saying on several occasions that the United States would defend Taiwan if China attacked. One close ally of the administration said that although White House officials have walked back those statements, Biden is intentionally sending a message to China when he makes such pronouncements.

Despite the diplomatic skirmish over the balloon and the tensions in the relationship, experts said Biden and Xi have both made clear they do not want to cut off communication or risk an escalation, as both countries still need each other and are keenly aware of the perils of a clash between the superpowers.

“There’s the Biden who says, ‘Rest assured, I understand foreign policy and I have this long history with Xi Jinping.’ But there’s also the Biden who says, ‘If I see a challenger on the horizon who needs to be corralled or slowed down, it’s China,’” said Rajan Menon, director of grand strategy at Defense Priorities. “But they realize a breakdown in communications or an outright confrontation would be bad for both sides.”