If you are looking for indicators about the state of politics this year, circle April 4 on your calendar and turn away from Washington. Look instead to Chicago and Wisconsin, where a pair of pivotal elections will offer clues about the strengths and weaknesses of the two major parties and the potency of two highly charged political issues, crime and abortion.

The contest in Chicago is for the mayor of the nation’s third-largest city. In Wisconsin, the election is for a seat on the state Supreme Court. Crime dominates the mayoral race; the future of abortion rights shapes the backdrop of the choice for Wisconsin voters.

Both elections are local and yet have implications beyond their boundaries as Republicans and Democrats prepare for competition in 2024.

The Chicago contest will highlight tensions within the Democratic Party about meeting the expectations of its progressive wing while confronting what has been an increase in crime in big cities that Republicans have sought to exploit. The Wisconsin contest will highlight the degree to which the issue of abortion, in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, remains a powerful motivator for Democratic voters and a political vulnerability for Republicans.

Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot (D), the first Black woman to hold the post as well as the city’s first openly gay mayor, lost her bid for a second term, running a distant third with only about 17 percent of the vote in a crowded field and thereby failing to make it to the April runoff.

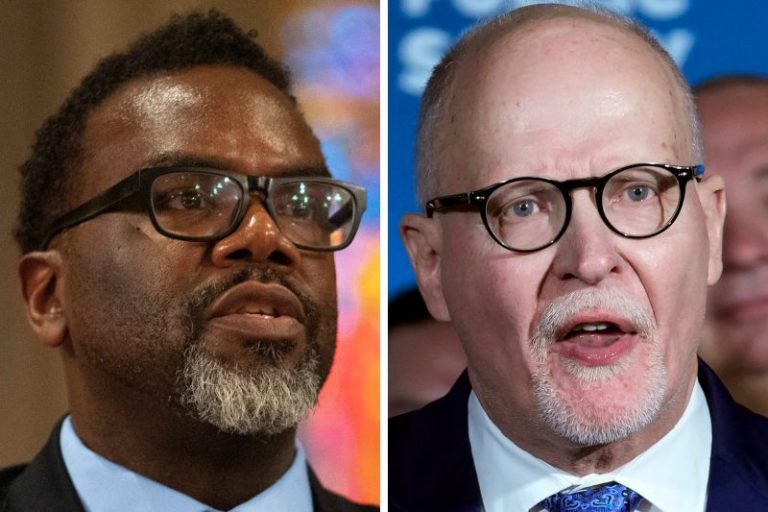

The two remaining candidates, moderate Paul Vallas and liberal Brandon Johnson, offer near-polar-opposite views on the issue of crime and in their bases of support. Neither came close to the 50 percent needed to win outright, and both will have to expand their base to win.

Chicago has been plagued by gang violence and shootings for years. It has also had high-profile episodes of police misconduct, including the 2014 police shooting of Laquan McDonald by officer Jason Van Dyke. As mayor, Lightfoot, a former prosecutor, rejected calls to “defund the police.” But on her watch, homicides spiked during the pandemic, hitting just over 800 in 2021. The number decreased to 695 last year but remained high, making crime by far the dominant issue in the election.

Other factors cost Lightfoot politically. Her time in office was marked by conflict and confrontation. She had few political allies and more than a few adversaries. Overwhelmed by the crime issue, she became the first mayor in 40 years to lose office after a single term.

The runoff between Vallas and Johnson has quickly become a testing ground for Democrats as they wrestle with tensions within their coalition over the issue of crime. Some Democratic strategists have warned that a failure to confront the issue directly makes their candidates vulnerable to Republican attacks.

Others decry that the party has yet to make good on promises to enact police reform. The mayoral runoff will also be a measure of how much public sentiment has shifted on that issue and the basket of issues that gained prominence in the months after George Floyd’s murder in 2020. Calls to “defund the police” gained steam through the Black Lives Matter movement. Although the push calls for shifting resources away from low-level crime and toward public needs, the slogan came with a political cost, and most Democratic elected officials have moved away from such rhetoric.

President Biden planted his flag on the issue long ago, rejecting calls in 2020 to defund the police and advocating for more money for policing during his campaign. A few days ago, he said he would sign a resolution promoted by congressional Republicans to block D.C.’s revision of sentencing laws in the capital, an issue that has put Democrats in Congress on the spot.

For the next month, Chicago will become the focus of a nationalized debate about how Democrats are dealing with crime and whether they can satisfy both their liberal and center-left constituencies on an issue that has caused them trouble over many years.

Vallas is no newcomer to Illinois politics. He ran unsuccessfully for governor in 2002 and was the candidate for lieutenant governor on the Democratic ticket in 2014 that went down to defeat. He has served as the CEO of Chicago’s public schools and as CEO of Philadelphia’s public schools.

In the mayoral race, he made crime his principal focus and was endorsed by the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP). That association proved politically valuable but also politically ticklish. The FOP endorsed President Donald Trump for reelection in 2020 and last month invited Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) to speak to officers at an invitation-only gathering. Vallas issued a statement expressing his disappointment, saying there was “no place in Chicago for a right-wing extremist” like DeSantis.

Johnson, a Cook County commissioner, is running as a progressive voice in the campaign. His candidacy surged late in the campaign, putting him in second place a few points ahead of Lightfoot but still well behind Vallas. He has been an organizer for the powerful Chicago Teachers Union and was endorsed by the CTU in the mayoral campaign. The union has sparred with previous mayors, and a Johnson victory would presumably give it significantly more power over city school policy.

Lightfoot ran ads attacking Johnson for past statements supporting calls to defund the police. He has since softened his language on the issue but says current policing practices have been a failure. But he also says adding more police is not the answer, advocating instead for more money toward housing and mental health.

Black and Hispanic voters hold the key to the election. Lightfoot ran ahead of everyone in Black precincts, while Rep. Jesús “Chuy” Garcia led among Hispanic voters. Johnson found his strongest support among White liberals on Chicago’s North Side, in precincts along Lake Michigan. Vallas won more conservative White voters in other parts of the city. Competition for Black and Hispanic voters will be fierce.

In last year’s midterm elections, Republicans focused on crime, immigration and inflation, and believed that those issues would produce a big majority in the House and a small majority in the Senate. They believed that the furor over the Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization had faded and that fears about disorder in the country would bring voters to their side. Instead, in considerable part because the anger over the court’s decision and concerns that Republicans had become an extreme party under Trump had persisted, they fell far short of expectations.

That history provides some of the backdrop to Wisconsin’s Supreme Court election.

Wisconsin remains a closely divided state politically. Trump in 2016 and Biden in 2020 each won the state by about one percentage point. But Republicans enjoy a big majority in the state legislature, thanks to gerrymandered legislative districts and Democrats’ weakness in rural areas that have shifted to the GOP. Democratic Gov. Tony Evers won a second term in November and can act as a barrier to the GOP legislators. But a shift in the liberal-conservative balance on the court would mark a major change in the state’s politics.

Supreme Court justices in Wisconsin are not elected by party. The court has a 4-3 conservative majority; a change to a 4-3 liberal majority could result in overturning an 1849 law banning virtually all abortions, and it could affect the legislative district boundaries.

The election has become a clear partisan battle, pitting liberal Janet Protasiewicz, a circuit court judge in Milwaukee County, against conservative Daniel Kelly, a former state Supreme Court justice. Within the boundaries of judicial elections, Protasiewicz has been open about her views on abortion, and both parties and their allies see the election as a major test.

In last month’s primary, Democratic turnout eclipsed that of the Republicans, even though the Republican primary was more competitive. A victory by Protasiewicz would signal to Republicans that the abortion issue has not faded and that it remains a potent weapon for Democrats.

The Chicago and Wisconsin elections are reminders of the significance of state and local politics at a time when government in Washington is divided and when prospects for significant action on big issues are slim.