A turncoat who didn’t represent Democratic values. A traitor who literally embraced a despised Republican. And a Democrat who promoted GOP agenda items.

Well, technically the person wasn’t even a Democrat, as the senator had become an independent to navigate politically treacherous waters back home.

But instead of heeding calls for punishment, the majority leader decided to cut “some slack” to the recalcitrant senator, who got to stay in the caucus and retained seniority on key committee assignments.

“This decision had not so much to do with forgiveness as it did with simple math,” Harry M. Reid (D-Nev.), then the Senate majority leader, wrote in an addition to his autobiography in 2009. “Years of counting votes in the Senate had taught me that you never take a vote for granted.”

Reid, who retired from the Senate six years ago and died of cancer last December, never served with Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (Ariz.). He was dealing with Joseph I. Lieberman (I-Conn.), the onetime Democratic vice-presidential nominee who had won a tough reelection in 2006 as an Iraq War-supporting independent and then supported the GOP presidential nominee.

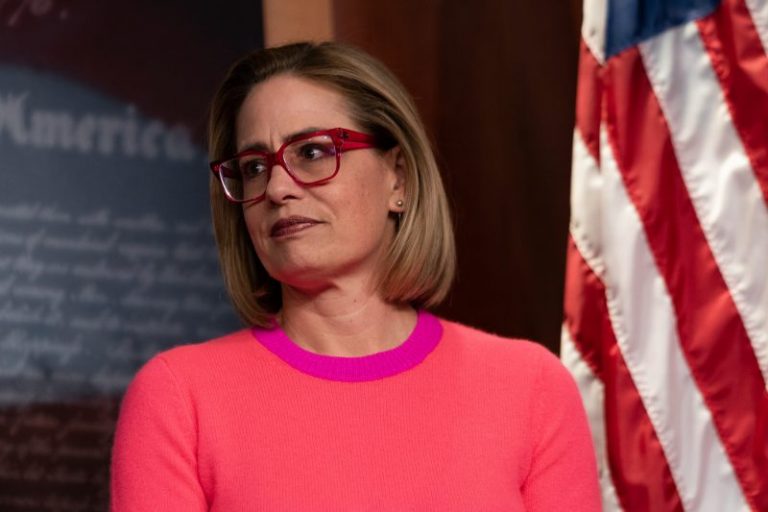

On Friday, Sinema — the centrist who has vexed party leaders with her support for conservative tax policy that benefits billionaires — formally left the Democratic Party. She had informed Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) the day before, but at the same time requested to retain the privileges of being a member of his caucus.

Schumer, like Reid 14 years ago, understands simple math: 51 is better than 50.

With her in his caucus, Schumer has a clear majority that gives Democrats full control of committees, subpoena power and the chance to more expeditiously move President Biden’s executive branch and judicial nominations.

They get to obliterate that 50-50 power-sharing Senate of the past two years and do not necessarily need Vice President Harris to keep up her modern record-setting pace for casting tiebreaking votes.

And for that Schumer will not care what label Sinema wants to use for the next two years. He just hopes she will continue to vote for a large portion of the Biden agenda and serve as an emissary to her many Republican friends when times call for a bipartisan compromise.

“I believe she’s a good and effective senator and am looking forward to a productive session in the new Democratic majority Senate,” Schumer said Friday in a statement released a few hours after her announcement.

For all intents and purposes, Sinema’s life won’t be any different in the Senate.

If you sit on the left side of the center aisle, you’re in the Democratic caucus; the right side is for the Republican caucus, and whichever side has more seats is deemed the majority.

Sinema’s position will be no different from those of the two other independents who caucus with Democrats, Sens. Angus King (Maine) and Bernie Sanders (Vt.).

Many liberals had a good-riddance reaction, especially after Sen. Raphael G. Warnock (D-Ga.) locked up the 51st seat by winning Tuesday’s runoff. That slightly lessens the power that Sinema, Sen. Joe Manchin III (D-W. Va.), or any Democrat could leverage on party-line votes.

“Kyrsten Sinema’s ability to be the center of the political universe has ended within the Democratic Party. This is a predictable outcome for Senator Sinema as she has entirely separated herself from any semblance of representing hard-working and struggling Arizonans,” Rep. Raúl M. Grijalva (D-Ariz.) said in a statement.

But Schumer treated her more kindly, lest she walk across the aisle to Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) for committee assignments and leave him again with a 50-50 Senate.

He’s following the long-game model that Reid took with Lieberman, as well as, to a slightly different degree, that McConnell has taken with GOP Sen. Lisa Murkowski’s politically independent maneuvers that have kept winning in Alaska.

It remains to be seen whether Sinema is as politically dexterous and can win reelection in 2024, the way Lieberman and Murkowski did without a major-party label, raising money on their own without party resources.

Lieberman’s drift away from the party began as the Iraq War turned bloodier with years of entrenched warfare and most Democrats recoiled at the Bush administration’s handling of it. But Lieberman dug in and fully supported an even deeper U.S. footprint in Iraq, just as he had done in his unsuccessful 2004 presidential bid. That campaign drew liberal protesters, including from a young, antiwar Arizonan named Kyrsten Sinema.

Ned Lamont, who later won the Connecticut governorship and continues to serve in that post, won the Democratic primary over Lieberman in 2006. But Connecticut had no sore-loser law, so Lieberman simply ran as an independent in the general election, while many Republicans backed away from their nominee.

Lieberman won in the general election by more than 10 percentage points with a coalition of many Republicans, centrists and a few Democrats. Nationally, Democrats won six seats and claimed a bare majority, 51 to 49, and Reid didn’t blink at the idea of rewarding Lieberman with the chairmanship of the Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee.

But in the 2008 presidential campaign, Lieberman crossed the aisle to back Republican presidential nominee, John McCain (R-Ariz.), and he campaigned forcefully against Barack Obama.

After Obama won, and Democrats had gained eight seats in the Senate, many wanted retribution. With close to 60 seats, they fumed to Reid: We don’t need Lieberman, kick him out of the caucus or at least strip his committee gavel.

When meeting with Reid after his reelection, Lieberman threatened to caucus with McConnell. Reid, in one of his most prescient moves, figured he could get bigger things done with Lieberman inside the tent, annoying as he might be to some liberals.

“As badly as he had behaved during the campaign it was a simple fact that apart from the war, Joe had a very solid progressive, Democratic record,” Reid wrote in April 2009.

Lieberman kept his Homeland Security Committee gavel but surrendered a less important assignment on a different committee. Eight months later, he voted for the Affordable Care Act, a high-wire act in which Reid needed all 60 votes in his caucus.

Lieberman called it one of his proudest votes. “The Affordable Care Act — for which I was the necessary 60th vote — was real and historic health-care reform,” he wrote in his own book.

In 2010, Murkowski served as a deputy on McConnell’s leadership team, but she got outflanked by a right-wing opponent and lost her primary. McConnell and other leaders issued tepid endorsements of the GOP nominee, but Alaska law allowed Murkowski to run a write-in campaign, so some GOP operatives shipped out to Alaska to help her pull off the upset win, behind a coalition built around independents, some establishment Republicans and a few Democrats.

She returned to the GOP caucus but not in leadership, preferring the freedom to focus on her committee work. She’s often a thorn in McConnell’s plans — she opposed Supreme Court Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh — but she’s often been there for him, particularly on the 2017 tax-cut plan.

And in November, she won reelection through Alaska’s new ranked-choice voting, which Murkowski helped usher into state law, a process that allowed her to win a fourth full term largely with Democratic support.

Sinema faces a much tougher path to reelection. Arizona is a sharply divided swing state with two parties that will not tacitly let their voters support a candidate with a different label, the way Democrats in Alaska, Maine and Vermont have done recently for Murkowski, King and Sanders.

Lieberman pulled off the political inside straight only once, in 2006. Ahead of 2012, a younger Democrat, then-Rep. Chris Murphy (Conn.), had lined up a challenge, and Republicans eventually nominated a billionaire.

Lieberman decided to retire. In that last term, he infuriated liberal Democrats by pushing for a smaller stimulus bill in 2009 and opposed a government-run insurance option in the ACA in 2010.

But he supported those overall packages, providing the key vote, just as Reid had hoped. It was simple math.

And Schumer has made the same calculation with Sinema.