In Kansas City, a former FBI analyst pleaded guilty in October to taking home more than 300 classified files or documents, including highly sensitive material about al-Qaeda and an associate of Osama bin Laden. She faces up to 10 years in prison. In Massachusetts, a defense contractor pleaded guilty in 2019 to removing classified national defense information from his office and storing it at home. He got 18 months.

And in Maryland, Harold Martin, a former government contractor, took home a huge number of hard and digital copies of classified materials — the equivalent of 500 million pages — though he never shared it with anyone. He is midway through a nine-year prison sentence.

“For nearly 20 years, Harold Martin betrayed the trust placed in him by stealing and retaining a vast quantity of highly classified national defense information entrusted to him,” U.S. Attorney Robert K. Hur said in a Justice Department news release in 2019. “This sentence, which is one of the longest ever imposed in this type of case, should serve as a warning that we will find and prosecute government employees and contractors who flagrantly violate their duty to protect classified materials.”

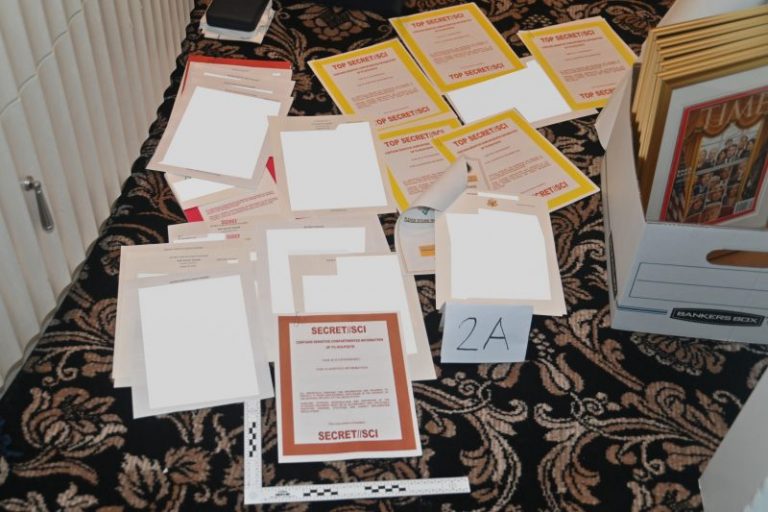

No U.S. president has ever been charged with a crime, and experts say any classified-documents prosecution involving a former commander in chief would be more complicated and fraught than the average case. But they also say past cases illustrate the potential legal exposure facing Donald Trump, who is under investigation for keeping thousands of government papers, some highly sensitive and more than 300 marked classified, at his Florida residence and popular private club.

The criteria for prosecuting people who improperly handle classified documents are clear: Prosecutors must prove a person deliberately flouted rules for how to store the material securely, while knowing it was classified or secret national defense information. They do not need to establish evidence that the person tried to sell the classified material or shared it with others.

“The person’s motive is more relevant to a defense for mitigation purposes than it is for prosecuting cases,” said Mark S. Zaid, a lawyer who has handled espionage cases.

The Justice Department has alleged that keeping or hiding the documents at Mar-a-Lago may have violated criminal statues — including a part of the Espionage Act, a broad law typically associated with spying but also covering anyone who “willfully retains” or “fails to deliver” national defense information. It is one of many criminal statutes that protects the country’s most secret information.

Trump has denied wrongdoing, telling his lawyers the material belonged to him, not the American people, according to people familiar with the conversations who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss them. He also has publicly claimed that he declassified the documents he kept — a scenario national security law experts say would require a careful process that there is no evidence Trump followed.

A Trump spokesman did not respond to a request for comment on Thursday.

The Washington Post reported in November that federal agents and prosecutors believe Trump had no financial or transactional motive for allegedly taking and keeping classified documents. People familiar with the investigation, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss it, said prosecutors believe Trump acted largely on his desire to hold on to the materials as trophies or mementos.

In the Maryland case, investigators similarly concluded that Martin, the government contractor, was likely a hoarder who had no intent of sharing or selling the country’s secrets.

Nor did prosecutors determine a clear motive in the Kansas City case involving Kendra Kingsbury, an FBI analyst for more than a decade who stored top-secret government documents at her home.

A lead prosecutor in that case — David Raskin, an experienced Justice Department national security attorney — was subsequently tapped by Attorney General Merrick Garland to assist in the Trump document investigation.

“Kingsbury knew that her personal residence was not an authorized location for such storage and having unauthorized possession of these 20 documents relating to national defense,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Patrick C. Edwards, one of Raskin’s colleagues, said at a hearing in that case, according to a court transcript. “She willfully retained the documents and failed to deliver them to an officer or employee of the United States entitled to receive them.”

In prosecuting government workers and contractors for mishandling sensitive information, prosecutors often rely on statements those individuals must sign to get security clearance, in which they pledge to follow classification rules. Martin admitted to investigators that he understood that keeping the documents at his home was wrong. In court filings, prosecutors emphasized that Kingsbury had been trained in how to handle classified documents and knew storing them at her home was prohibited.

Presidents don’t go through that same paperwork process. So to bring a case against Trump, prosecutors would need to show that he was aware storing the documents at Mar-a-Lago could be a crime.

Legal experts said the government has enough documentation — from requests for documents from the National Archives and Records Administration to subpoena demands by the Justice Department — to prove that Trump knowingly failed to return sensitive materials back to the government.

“The president does not have a clearance, he is effectively cleared by process of being elected. So if there was indictment for Trump it could not simply be copy and pasted from previous indictments,” said Steven Aftergood, a longtime specialist in the handling of classified information. “But that does not mean he could not have willfully retained records or failed to deliver them. If nothing else, the subpoena that was rendered to him made it clear that he had an obligation to return these records.”

The Justice Department is also exploring possible charges of obstruction or destruction of government property. People familiar with the investigation have said a Trump aide told the FBI the former president instructed him to remove boxes from a storage room where classified documents were kept — and that was done after Trump received a subpoena in May for any classified material in his possession. Investigators also have obtained video surveillance footage showing boxes being moved, said these people, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the probe.

The Post has reported that some of the top-secret material kept at Mar-a-Lago involved nuclear programs, while other documents focused on Iran’s missile system and intelligence gathering in China, according to people familiar with the matter who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss it. The highly restricted nature of those documents helped convince the FBI to launch its initial investigation, if only to get the material back under government lock and key.

Most cases of government workers or contractors who mishandle classified documents are handled administratively with wrongdoers losing their jobs and clearance to handle sensitive documents. Zaid said he has represented several clients who fit that profile, accidentally taking classified materials home as they cleaned out their desks, for example. One client unintentionally left some classified material in his car while he went inside a fast-food restaurant.

Martin and Kingsbury, in contrast, hoarded millions of pages of restricted material in their homes over their careers, triggering criminal investigations. And Ahmedelhadi Serageldin, the Massachusetts defense contractor, downloaded hundreds of classified documents onto an external hard drive, which his employer — Raytheon Technologies — noticed while investigating him for timecard fraud.

When FBI agents searched Martin’s property, they discovered classified materials haphazardly scattered across his property — stored in his home office, in an unlocked and dusty shed in his backyard and in his car, according to court documents.

“What began as an effort by Mr. Martin to be good at his job, to be better at his job, to be as good as he could be, to see the whole picture at his job, became something more complicated than that. It became a compulsion,” Martin’s attorney, James Wyda, said in a 2016 court proceeding. “It got a grip on Mr. Martin. … This was not Spycraft behavior.”