As he considered retirement, Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) cited competing verses from the Old Testament and the New Testament. From Ecclesiastes, he read that there was a “time to” move on, but from Galatians, he heard the call to keep marching on.

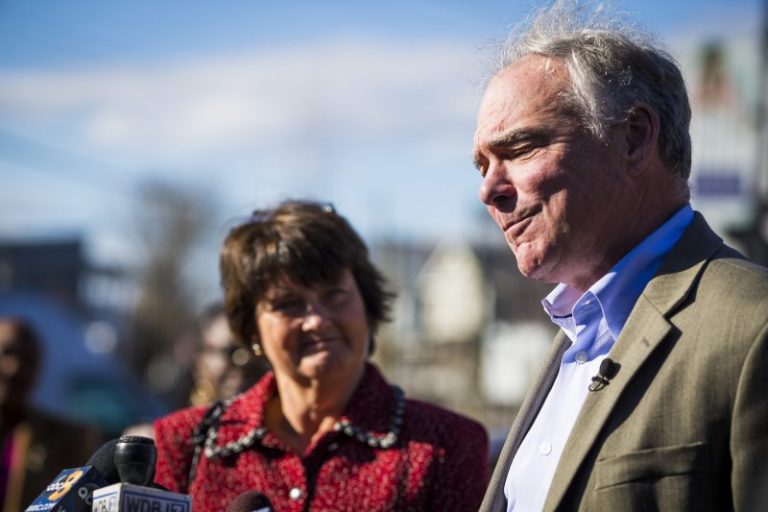

“Do not grow weary in doing good; you will reap a great harvest if you do not give up,” Kaine said Friday in Richmond, paraphrasing the New Testament verse that he said guided him in his decision to run for another six-year term in 2024.

It’s a near-perfect metaphor for life in the Senate: growing weary, plodding along, waiting and hoping for the big legislative rewards to finally be harvested. Toss in the coarsening political environment, driven by 24/7 cable news and social media fixation on the politics of instant gratification, and it’s not a big surprise that Kaine came very close to finding “a time to give up.”

Kaine’s near departure prompted a bit of a fire drill for Democrats, fearful that the already difficult 2024 campaign map would get even trickier if the popular two-term incumbent had opted to retire.

But it also created the fear that the Senate would lose another one of its workhorses who try to find bipartisan compromises, following last year’s departure of a handful of Republicans who traditionally worked across the aisle.

Four others in the Democratic caucus — Sens. Angus King (I-Maine), Joe Manchin III (D-W. Va.), Kyrsten Sinema (I-Ariz.) and Jon Tester (D-Mont.) — all face decisions in the coming months about running again after playing key roles on bipartisan bills last Congress.

Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah), who will be 77 on Election Day 2024, also must decide whether to seek another term after his leading role as a GOP dealmaker.

Even if they do run, several of these centrists expect to face very difficult reelections in 2024 and might not return.

Last year’s GOP retirements, coupled with this year’s reelection decisions and next year’s elections, could eviscerate the Senate’s core center that has served as the legislative hive. A rotating cast of more than two dozen senators served in bipartisan “gangs” that functioned as rump caucuses that drove legislation into law.

Beginning in late 2020, a bipartisan group of nine senators produced a framework for what became a $900 billion pandemic relief package. By summer 2021, an evenly divided group of 20 senators paved the way for what turned into a more than $1 trillion infrastructure package.

The final pieces of legislation designed to kick-start the domestic semiconductor industry came together through bipartisan talks among key rank-and-file senators. That came just after a group of two Republicans and two Democrats forged the first modest form of gun control legislation since 1994.

The same thing happened on bills codifying rights to same-sex marriage and revamping election laws to try to prevent another attempt at overturning presidential elections like the Jan. 6, 2021 riot at the Capitol.

That productivity served as a driving force in tipping Kaine’s decision toward the New Testament and seeking another term.

“The Senate is frustrating. Things don’t move fast,” he told reporters in Richmond, ticking off some of the recent successes both for Virginia and the nation. “I think we’ve hit [a] stride and I think I’m getting better at it. Because it’s a weird place, the Senate, you have to learn to get better at it.”

Those bipartisan efforts, however, serve as both moments to congratulate the dealmakers and as an ongoing repudiation of how the Senate continues to falter from its original design.

None of those successes came through “regular order,” as old-timers like to call it. It’s the type of process made famous by the Schoolhouse Rock anthem “I’m Just a Bill” that taught children that bills started in committee, passed the House, then the Senate and then a compromise got hatched and needed to pass each chamber again.

That process has withered on the vine the last decade, as congressional leaders, particularly in the Senate, have claimed more power away from committee rooms.

Derek Willis, now a journalism professor at the University of Maryland, built a database five years ago monitoring congressional action for a project jointly produced by The Washington Post and Pro Publica, showing the atrophying nature of legislative debate.

In Harry M. Reid’s first term as Senate majority leader, 2007-08, the Nevada Democrat allowed almost 64 percent of all votes to come on amendments to legislation. Amendments used to serve as the bread and butter of what a rank-and-file senator can do to participate in the system. In Reid’s last term as majority leader, 2013-14, less than 22 percent of votes came on amendments.

In his first term as majority leader, 2015-16, Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) allowed 53 percent of all votes to come on amendments. That fell to a record low of less than 10 percent in his last term in 2019-20.

In 2021 and 2022, Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) opened up the chamber a little bit more than McConnell, according to Willis’s database. More than 23 percent of all roll calls came on amendments.

But many of those amendment votes came during the four sessions, each over about two days, when Democrats used a parliamentary device to pass two massive bills on party-line votes — in exchange, they had to allow an almost unlimited amount of amendments to be presented.

Otherwise, most legislation got considered with very little input from rank-and-file senators, unless they happened to be part of the “gang” working out the compromise.

Even popular bipartisan bills don’t see the same light of day. The national Pentagon policy bill, which used to receive about two weeks of time on the Senate floor for debate and amendment, got a few hours of consideration last month, a couple of amendment votes and then final passage.

That lack of robust activity prompted senators like Romney, Sinema, King and recently retired Rob Portman (R-Ohio) to create these informal bipartisan huddles on issues like infrastructure.

If these so-called gangs are going to continue to flourish, they need critical mass in terms of senators willing to participate. Portman’s replacement, Sen. J.D. Vance (R), has embraced the far-right, anti-establishment ethos that doesn’t lend itself to working across the aisle.

Roy Blunt (R-Mo.), now retired after years of working collegially with Democrats on the Appropriations Committee, has been replaced by Sen. Eric Schmitt (R), who spent much of his GOP primary last year trying to win an endorsement from former president Donald Trump.

The Republicans who have already jumped into challenges to Tester and Manchin come from the MAGA mold of the party, creating the potential to dramatically shift the ideological balance should they replace those centrist Democrats in January 2025.

Kaine has seen his own personal ambition — a congressional rewrite of the 2001 and 2002 war resolutions to update the rules of engagement for the current battlefield — languish as committee chairs have been unable to persuade Senate leaders to devote floor time to what would be a cumbersome and time-consuming debate.

In deciding to run for another term, Kaine signaled that he wants to see those successful bipartisan groupings to keep up their work. He even suggested that the path to an overhaul of immigration and border laws could come that way.

He may have to take a more leading role in those types of talks now that so many Republicans have retired and his Democratic colleagues ponder doing the same or running difficult reelection races.

Kaine has the résumé — mayor, governor, national party chairman, vice-presidential candidate, senator — with the gravitas to take charge.

“Having made the decision, I’m all in,” he said Friday.

The bigger question might be whether, in another two years, there are enough senators like him to reap the legislative harvest from the hard work.