PHILADELPHIA — This historic city has long fueled Democratic victories in Pennsylvania, helping candidates for president, governor and U.S. Senate run up huge margins to offset Republican advantages across most of the state.

But more recently, the once strong election engagement by Philadelphia’s voters has been waning. In the 2022 midterms, when turnout rose statewide, just 43 percent of voters in the city cast ballots, down from 49 percent in 2018. And on May 16, when the city had a high-stakes mayoral primary that drew record spending, just 32 percent of Philadelphia’s nearly 800,000 registered Democrats turned out, according to the Philadelphia City Commissioners.

“I’m not feeling good. I thought the competitiveness would increase turnout,” Bob Brady, a former congressman and longtime chairman of the city’s Democratic Party, said as he sat in his front office around noon on the day of last month’s primary, his cellphone to his ear, a half-eaten hoagie on the table. “We do everything we can — the apathy is just there.”

It’s an ominous trend for Democrats, who have seen participation dip nationally among core supporters like Black voters, who make up a large share of the electorate in urban areas like Philadelphia. Low turnout in Milwaukee contributed to Democrats losing Wisconsin’s U.S. Senate contest in last year’s midterms. Black voter turnout nationwide dropped by nearly 10 percentage points in 2022, from 51.7 percent in 2018 to 42 percent, according to a Washington Post analysis of the Census Bureau’s turnout survey.

In 2022, the Democrats who led the ticket in Pennsylvania, Josh Shapiro for governor and John Fetterman for Senate, benefited from deeply flawed opponents and top-tier campaign operations. Both men overperformed in the Philadelphia suburbs and in White, working-class areas around the state, where Democrats have struggled in recent years. Their success elsewhere in the state allowed them to win overwhelmingly despite the lower turnout in Philadelphia, where Democrats outnumber Republicans 7 to 1.

Joe Biden overperformed in the vote-rich Philly suburbs in 2020, winning by a margin of over 100,000 votes more than Hillary Clinton got in 2016 to offset a narrowing advantage in the city. It was enough to give him a slim victory in Pennsylvania and secure the White House. Democratic strategists and activists are concerned that weak turnout in Philadelphia could hamper Biden’s chances in 2024. Democratic Sen. Robert P. Casey Jr. is also up for reelection next year.

“Philly is the engine of Democratic success in Pennsylvania, and when it isn’t performing, Democrats have lots to worry about,” said Chris Borick, a veteran pollster at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pa. “If I’m a Democrat right now, I’m worried about what’s happening in Philadelphia and its broader effect on the electoral math. It’s vexing for the party in a place where stakes couldn’t be higher.”

In interviews with more 30 people across the city this spring, many voters said they have lost faith in their leaders, some of whom have been involved in city or state politics for decades. The city’s ward system, where many of these leaders got their start, also hasn’t been able to drive votes as well as it did in the past.

Many residents expressed pessimism that casting a ballot would lead to change.

“I never voted in my life because I don’t have faith,” said Siddeeq Bowie, 23, a basketball coach at Lighthouse Community Center in the 7th Ward in North Philly, where voter turnout is consistently among the lowest in the city. “Nothing changes. It’s always the same stuff, you know?”

Brady, an imposing figure at over 6 feet tall, has presided as party boss in this town for nearly 40 years. On the day of the mayoral primary, the 78-year-old was on the phone with former Pennsylvania governor and Philadelphia mayor Edward G. Rendell, who was seeking updates on turnout.

“People don’t vote. People don’t want to vote,” Brady said he told Rendell, shaking his head. He sighed. “I’ll let you know.”

This year’s turnout, while up from the 25 percent of voters who participated in the 2019 mayoral primary, was still well below the 42 percent average for contested mayoral elections since 1983, according to a Washington Post analysis of available data.

Some blame the low engagement on Brady and a Democratic political machine that for decades got people to the polls but doesn’t operate with the power and efficiency it once did.

.

The city has 66 wards, which are broken up into smaller divisions. Voters in each of those divisions elect two Democratic and two Republican representatives, known as committee people, who in turn select ward leaders. Together, these neighborhood officials are responsible for educating voters and getting them out to vote. They were also known for helping get potholes filled or putting in a good word for someone applying for a city job.

Meanwhile, young, liberal activists who have moved into gentrified neighborhoods in the city cite a lack of vision and citywide coordination to mobilize voters. Others have argued that low voter turnout actually allows party leaders to hold on to power and have sought to challenge the traditional system, in which ward leaders control candidate endorsements and funds, in favor of a more open, democratic system of running ward business. In one neighborhood, for instance, some committee people accused the longtime ward leader of shutting them out of meetings and not sharing information with them. The group sued, and a judge ordered the leader to work with all ward officials.

“The basic fact was just people didn’t know what the ward structure was,” said Democratic state legislator Nikil Saval, who helped lead a takeover of the 2nd Ward in 2018 by a more liberal wing of Democrats. “They didn’t know what wards did, and largely that’s because they didn’t do that much.”

Critics say an aging population and the changing demographics of neighborhoods have scuttled once stable voting blocs and the activism that long fueled voter participation.

“In a city like Philadelphia, which is plurality Black, there needs to be more investment in how to reach these voters and more of a commitment to a current and empowering message,” said Joe Hill, a Philadelphia Democratic strategist. “Most of the messaging we see targets the generation before mine — the civil rights generation. It focuses on the legacy of honoring the vote, the people who died, and the people who suffered the consequences.”

After the excitement of the Obama era, Hill said, there’s been an emerging cynicism among younger Black people who didn’t see “the quality of life in their neighborhoods improving in any real way” — not even with the first Black president. Their feelings soured more with the election of Donald Trump and more overt racism that has emerged in recent years.

“This has real implications for how we communicate, engage and mobilize,” said Hill, who helped create the Black Leadership PAC to fill what he sees as a void in harnessing the voting power of Black people.

Brady acknowledged some of the party’s problems, like a slowness to adapt to the internet and social media, and said he’s hired young people to help. He said he was at a loss for why voters were not coming to the polls. “I don’t know,” Brady said. “I wish I would know. I would try to do something to increase it.”

Many Philadelphians share a deep-seated perception that elections don’t make a difference in people’s day-to-day lives, said Lauren Cristella, interim president and chief operating officer of the Committee of Seventy, a nonprofit that advocates for citizen engagement and government reform.

“Their lives aren’t getting better,” she said. “The issues aren’t getting solved.”

As Latifah Smith, 28, a behavioral health and human services major at the Community College of Philadelphia, put it: “You still have the same people in power, same people doing the same thing. Nothing is really changing.”

‘We’re doing our part’

Naomi Swint, 95, remembers when her Northwest neighborhood used to be abuzz with activity during election season. Neighbors volunteered with the ward to canvass the streets, educating one another about the candidates as they worked to get more Black politicians elected into city government. Back in the 1960s, people saw their party ward leaders as go-to sources they could call in the middle of the night to solve problems in the neighborhood, she said.

Swint worked with her ward for decades, but about 20 years ago, she noticed that many of those pre-election activities had faded. The intensity of activism, the level of engagement and the get-out-the-vote energy changed.

“I don’t think anybody’s doing what they used to do,” she said, leaning forward slightly to emphasize her point. “Honestly, I don’t think so.”

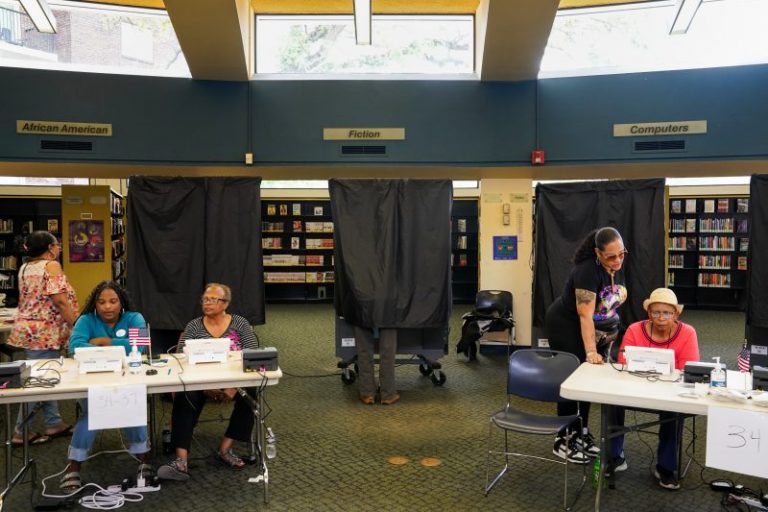

By midafternoon on the day of the mayoral primary, most divisions had seen only a couple dozen people cast ballots out of several hundred registered. “You can lead them to water, but you can’t make them drink,” Brady said to one poll worker during a quick stop at a polling place inside the Overbrook Library, greeting nearly every election worker with hugs and handshakes. “We’re doing our part.”

But sitting at a table checking in voters in the Divinity Hall community center where several divisions had polling spots, Michella Crosby, 70, and Ava Browning, 65, complained that committee people no longer took their roles seriously.

“You know what it is, if you’re a committeewoman, you’re a committeeperson in your division, you are supposed to know almost everybody,” said Crosby, who had been a committeeperson for four years. “Like when they come in, I know who they are,” she said, referring to voters.

“Number one, they have to be committed,” Browning said. “You got to get out there and show yourself so they can support you. If you’re not out there showing yourself …”

“Then nobody knows you,” Crosby said, finishing the sentence.

Former Philadelphia mayor Michael Nutter, who led the city from 2008 to 2016, said the lack of voter engagement now reflects a lack of energy from politicians and party leaders.

“I have this theory that cities are living, breathing, sensitive organisms, and that they have moods and attitudes. They take on, to some extent … I don’t want to say persona, but what comes out to them from the top leadership,” he said in an interview. “And, you know, it feels like there’s not a whole lot happening in our city.”

Rendell, who was the city’s mayor from 1992 to 2000, said Philadelphia’s Democratic Party is not alone in struggling to adapt to demographic and cultural changes in urban areas.

“No city committee, in any city, is as effective as it used to be,” Rendell said in an interview. “In the old days, people depended on their city committeeperson to get a streetlight fixed or help with a traffic ticket. … None of that exists anymore.”

Although Brady, as party chair, bears some of the blame, Rendell said, there have been changes in how people get their information about candidates and elections. In the past, he said, “committee people were responsible for informing voters, and that’s how you got your political information. Now there’s political news on 24 hours a day, people don’t need the committeemen to tell them what the issues are.”

The aftermath of Trump’s win got people engaged and involved, Saval said. But those who waded into the ward organization said they viewed the party establishment as rickety and more focused on rewarding loyalty than on voter turnout.

“They felt like local party politics was not working and that they could do just as good, if not better a job than the existing, kind of, people and infrastructure,” said Saval, who emphasized creating momentum by knocking on doors and spreading their organizers’ message.

That discontent grew, he said, into a movement of committed volunteers and staffers for left-wing advocacy groups like the Bernie Sanders-inspired Reclaim Philadelphia, started by veterans of the presidential campaign for the senator from Vermont. That energy also flowed to political entities with a similar ideology, like the Working Families Party, which captured an at-large city council seat in 2019 that had been held by a Republican for decades.

Yet these insurgent Democrats fell short in the unusually tight contest for Philadelphia’s 100th mayor, which had nine candidates. Their preferred candidate, former city council member Helen Gym, came in third behind the winner, fellow council member Cherelle Parker, and former city controller Rebecca Rhynhart.

In a statement two days after the primary, Brady touted the victory of Parker, who is Black and could become Philadelphia’s first female mayor, and was the establishment favorite in the primary. Brady blasted critics who he said saw the party as “a relic of the past, a dinosaur.”

Parker won with 32 percent of the 281,000 votes cast, a small fraction of the city’s 775,000 registered Democrats. Brady, who had bemoaned the low turnout a couple of days earlier, declared that “the dinosaur roared.”

Lenny Bronner, Scott Clement and Alice Crites contributed to this report.