On Friday morning, the Justice Department released a report detailing the failures of the Minneapolis Police Department. The federal assessment began after police in the city killed George Floyd in May 2020 and determined that Floyd’s death was a function of “systemic problems” within the department.

The department “unlawfully discriminates against Black and Native American people in its enforcement activities,” the report found, validating many of the criticisms amplified in the protests that followed Floyd’s death. It wasn’t just that Floyd was a Black man who died at the hands of police; it’s that he died while being restrained by a member of a force that federal observers say systematized excessive force and targeting of Black people.

Each time there is a similar scenario, in which a Black person is victimized by a member of law enforcement, the incident is compartmentalized by many Americans. It isn’t that Black people are unusually victimized by law enforcement, it’s that Derek Chauvin, the officer who killed Floyd, is a bad apple. He’s the exception.

The response to the Justice Department report, if treated seriously at all, will probably just kick that excuse up a level. It’s just this one department that had issues, and those issues are being addressed. Problem solved.

This, in a nutshell, captures the politics of race in the United States. On the left, repeated demonstrations of systemic disadvantages for minority groups, particularly Black people, are viewed as part of an endemic problem for the country. On the right, they are treated as isolated examples — aberrations in a country that has moved well beyond its racist history.

It is useful for the right to treat them that way.

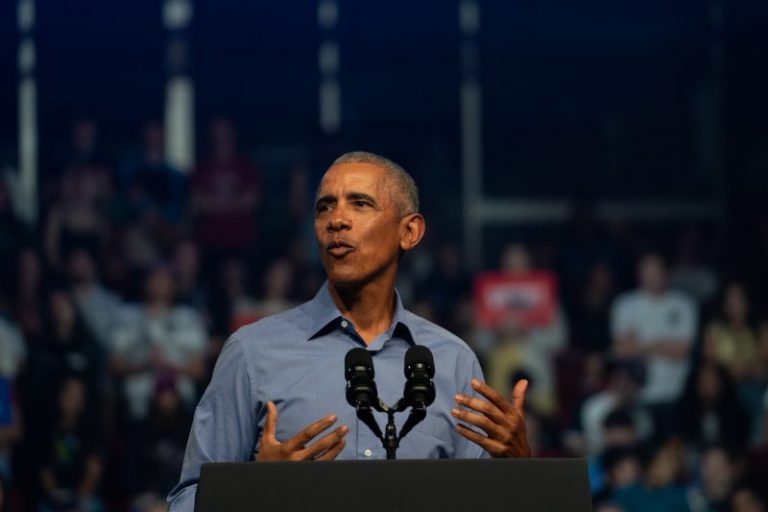

This week, former president Barack Obama appeared on his former aide David Axelrod’s CNN podcast. The two discussed how non-White Republicans — including Sen. Tim Scott (R-S.C.) and former South Carolina governor Nikki Haley — broached the subject of race.

Axelrod noted that Scott’s pitch often sounded like Obama’s famous speech at the 2004 Democratic convention, in which he noted that his own success was attributable to the progress the country had made. But Scott then takes it in a different direction, Axelrod said, saying that racism and discrimination are “part of the past and we don’t need to worry so much about it.”

“I think there is a long history of African American or other minority candidates within the Republican Party who will validate America and say everything’s great and we can all make it,” Obama replied. Celebrations of success, he continued, instead need to be “undergirded with an honest accounting of our past and our present.”

“If a Republican who may even be sincere in saying ‘I want us all to live together’ doesn’t have a plan for how do we address crippling generational poverty that is a consequence of hundreds of years of racism in the society and we need to do something about that,” Obama said, “if that candidate is not willing to acknowledge that, again and again, we’ve seen discrimination in everything from getting a job to buying a house to who the criminal justice system operates for, then I think people are rightly skeptical.”

But, again, this argument is rooted in the divide shown in the response to issues such as Floyd’s death. The ideas that poverty is rooted in racism or that there is systemic discrimination in the criminal justice system aren’t universally held. Washington Post-Ipsos polling released on Friday shows that 8 in 10 Black Americans think that the country’s economic system is stacked against Black people. Only 4 in 10 White Americans agree — as do only 2 in 10 Republicans.

If you’re Tim Scott or Nikki Haley, then, there’s no political utility in suggesting that racism is ongoing. Instead, each does what Axelrod indicated, suggesting that their own success is a demonstration that systemic obstructions are unimportant.

In a statement to the New York Post responding to Obama, Haley insisted that, in America, “hard work and personal responsibility matter.” Her parents, she continued, “raised me to know that I was responsible for my success.”

In an interview on Wednesday with right-wing commentator Mark Levin, Scott made a similar case.

“We should thank God almighty that this nation has afforded me, a kid raised in that single-parent household — not just to rise out of high school or to college, but to start my own business and to live my version of the American Dream,” he said. “It is possible, actually probable, that if you get a good education, that is your key to success in America. Mark, the thing you and I both understand and we embrace: The future of America is not determined by the color of your skin, but by the quality of your education, by your grit, your talent and your character.”

Examples of discrimination or systemic racism, of which there are many in the United States, are siloed as exceptions. Scott’s election as one of a handful of Black senators in U.S. history, though, wasn’t an exception: It was proof that equal opportunity exists. That systemic meritocracy is real.

Again, though, what are people who are seeking the Republican presidential nomination (as Scott and Haley are) going to say? The Republican Party is overwhelmingly White and older, overlapping characteristics that not only incline them toward skepticism about the problem of racism against Blacks, but instead provide fertile soil for thinking that it is White Republicans who face serious discrimination.

Axelrod and Obama discussed the role race played in the overwhelming opposition Obama faced as president.

“I think it’s fair to say that something like the tea party does not get the traction, does not generate the heat that it does,” Obama said, “had it not been for the fact that I represented something that looked like something very foreign to people, to some people, and scary.” Conspiracy theories that he wanted to impose sharia law probably wouldn’t have gotten the same traction had Joe Biden been president, he said.

The former president noted the United States’ shifting demographics.

“If you look at third-graders in the United States, the demographic there is really different than folks our age,” Obama said. “And so the country is becoming much more diverse, much browner. And, you know, that’s going to be scary for … folks who feel as if that means something’s being taken away from me.”

This sense of America changing away from conservative Whites is potent. “Make America great again” is an explicit appeal to an America that was, not the one that is. And if you are convinced — by treating your own experiences as norms instead of exceptions or by a right-wing media working feverishly to stoke the idea — that the country is changing in ways that give more power to other groups, you will undoubtedly be less sympathetic to the idea that those groups are blocked from power.

“There may come a time where there’s somebody in the Republican Party that is more serious about actually addressing some of the deep inequality that still exists in our society,” Obama told Axelrod, inequality “that tracks race and is a consequence of our racial history. And if that happens, I think that would be fantastic. I haven’t yet seen it.”

To Levin, Scott articulated an alternate, not uncommon presentation of how his political opponents use race.

“The radical left weaponizes the issue of race,” Scott said. “Whenever they find themselves in a bind about racial progress, it is about using race as a weapon for control.”

Which of those two messages is more likely to earn votes from a conservative primary electorate?