Ohio voters on Tuesday rejected a much-watched ballot measure that could have helped Republicans restrict abortion rights.

Red-leaning Ohio becomes the latest in a succession of states to deliver a setback to antiabortion forces after Roe v. Wade was overturned last year.

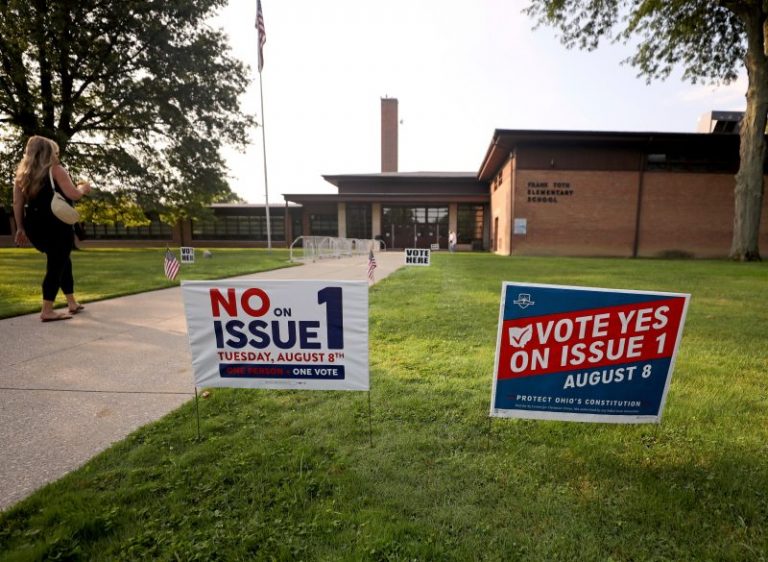

Ohio special election

End of carousel

The ballot measure, State Issue 1, would have raised the threshold for amending the state constitution via ballot measure to 60 percent, from the current 50 percent plus one. Its Republicans backers made clear the measure was meant to head off a November vote on a state constitutional amendment guaranteeing the right to an abortion. Such votes have cleared 50 percent even in red states.

With an estimated 61 percent of the vote counted, the measure trailed 57 percent to 43 percent.

Below are some takeaways from the vote and what it means:

The ballot measure wasn’t explicitly about abortion, but it was no secret that’s what it was really about.

And thus, it’s another sizable loss for antiabortion forces in the ballot wars.

The abortion rights position had won in all six states that featured such ballot measures after Roe was overturned last summer, including taking between 52 percent and 59 percent in a trio of red states. So with a constitutional amendment guaranteeing abortion rights set for Ohio’s ballot this November, Republicans tried to preemptively raise the threshold for passing it and other measures to 60 percent.

They came up very short, leaving Ohio much more likely to soon join those six states in having voters side with abortion rights post-Roe. (The other six: California, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Montana and Vermont.)

Given how those states voted — the measures in Kansas, Michigan and Kentucky dealt specifically with constitutional rights to abortion — it seems logical that between 50 and 60 percent of Ohio voters will favor the November amendment.

Some polls have even suggested an abortion rights amendment has a chance to clear 60 percent regardless of whether that was the required threshold. Two polls have pegged support as high as 58 percent, with plenty of undecideds.

Imagine the message it would send about the unpopularity of abortion bans if both this gambit failed and then the November amendment cleared 60 percent anyway.

While perhaps not likely, it’s possible, and Ohio Republicans have helped make it so.

The 2024 election is looking tight; the polls show Donald Trump’s indictments don’t appear to have changed that.

But when voters have actually voted this year, the signs have been much more encouraging for Democrats. And that continued Tuesday.

Democrats this year have over-performed even their good 2020 election results in a strong majority of special elections this year — by an average of more than seven points, per a Daily Kos Elections compilation. That continues a trend that began almost instantly upon Roe being overturned last year.

It’s a little more difficult to handicap what the Ohio vote says about where things stand between the parties. This wasn’t a strictly partisan choice, after all, and it’s hard to know how many people know this was about abortion.

But it’s certainly the latest evidence that the Supreme Court sending the issue back to the states — and what Republicans have attempted to do with that — has turned into a strategic liability for the GOP. Liberals also notched a huge win in a pivotal Wisconsin Supreme Court race in April that focused heavily on what the court might do on abortion rights.

The high turnout Tuesday for what would otherwise have seemed to be a technical change to state law in what is usually a low-turnout time of year suggests this vote animated people. And it yet again animated them in a way Republicans would prefer it didn’t.

It’s evident that this ballot measure wasn’t a particularly well-founded effort. But some invested more in it than others.

At the top of the list of the biggest losers Tuesday was Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose (R), who made himself the face of the initiative and is now running for Senate to unseat Sen. Sherrod Brown (D). LaRose appeared to want to burnish his conservative bona fides — and perhaps GOP voters will give him credit for trying — but a primary opponent has already been attacking him for alleged strategic failures.

Another loser would be former Arizona gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake, who traveled to Ohio this week to rally support for the measure. Lake’s attempted assistance was in contrast with other Republicans, who kept their distance.

The effort was also extensively financed by one man, conservative Illinois GOP donor Richard Uihlein, who provided $4 million of the nearly $5 million raised by Protect Our Constitution, the main group supporting the measure, and playing a large role in getting it on the ballot.

What’s also notable about this gambit is how desperate it appeared in the first place.

Not only did it seem to be a transparent workaround, but plenty of recent history has shown voters rejecting this kind of thing.

FiveThirtyEight’s Nathaniel Rakich noted that Republicans in several states in recent years have tried to increase the thresholds to pass ballot measures, in the face of popular ballot measures pushed by the left.

Raising the threshold to 60 percent failed last year in both Arkansas (where it got 41 percent of the vote) and South Dakota (where it got just 33 percent). Raising it to 55 percent also failed in South Dakota back in 2018.

There is one state that successfully raised its threshold recently: Arizona in 2022. But the measure was narrowly about ballot measures that raised taxes. And even that seemingly much more attractive idea — who likes raising taxes? — received only 51 percent of the vote.

Perhaps voters don’t like having power taken out of their hands.

That doesn’t mean it won’t be attempted again. But in Missouri, where Republicans are also floating this idea in the face of a 2024 ballot measure to ensure abortion rights, there appears to be some uncertainty about pressing forward.

And for good reason.