Late last month, the office of special counsel Jack Smith unexpectedly produced a new charge in the indictment of former president Donald Trump for allegedly possessing national security material at his Mar-a-Lago home.

It was understood from the initial allegations that Trump had allegedly sought to prevent the government from knowing about or taking possession of a number of documents he’d taken with him when he left the White House in January 2021. The new charge, though, offered a detailed allegation of one way in which that coverup manifested, with a minute-by-minute depiction of how Trump staffers allegedly sought to delete surveillance footage that the government had subpoenaed.

In a court filing released Tuesday, the reason for the new charge became clear. After the initial indictment, the staffer in charge of technology at Mar-a-Lago dropped the attorney Trump was providing him. After doing so, his sworn testimony changed, implicating Trump and other Trump staffers.

The filing presented by Smith’s office is a response to a nuanced legal fight over the use of a D.C. grand jury in relation to charges brought in Florida. The evolution of the technology staffer’s testimony is meant, in part, to demonstrate why that grand jury was employed: It’s where the staffer’s original, allegedly false testimony was offered.

The staffer at issue has been identified as Yuscil Taveras, named in the original Florida indictment as “Trump Employee 4.” That’s how he is labeled in Tuesday’s filing as well.

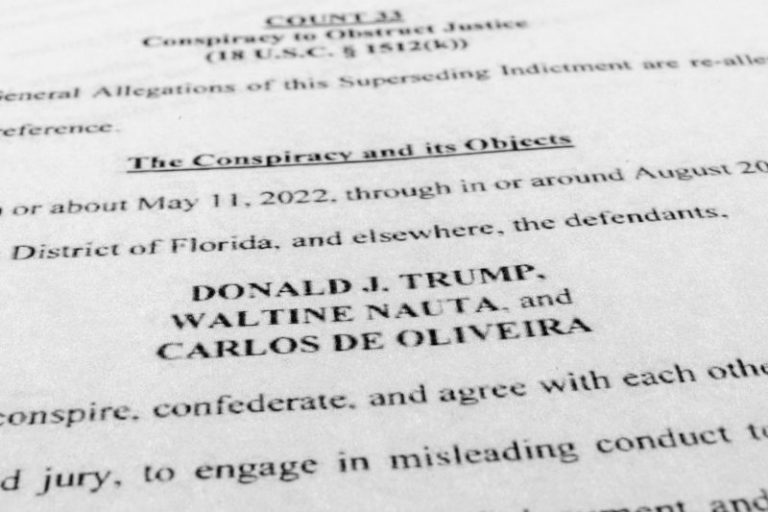

Over the course of the government’s investigation into Trump’s retention of documents (a probe that largely preceded Smith’s involvement), investigators obtained evidence indicating that Walt Nauta, a Trump aide who moved from the White House to Florida with him, and Carlos De Oliveira, a Mar-a-Lago employee, had sought to delete the surveillance footage the government was demanding in a June 2022 subpoena.

Taveras and De Oliveira offered testimony before the D.C. grand jury denying that they had discussed deleting any footage or claiming not to remember details of any such conversation. According to the filing, the government knew that this testimony was false.

Here’s where the problem arose. Taveras and De Oliveira were represented by the same attorney, Stanley Woodward, whose fees were being paid by Trump’s political action committee. When the government informed Taveras through Woodward in June that he was the target of a perjury probe, Woodward had a conflict. If he let Taveras reverse his testimony, his other client, De Oliveira, would be implicated. If he didn’t, Taveras would remain at legal risk.

The government noted the conflict to the court and Taveras was offered independent counsel, which he accepted.

“On July 5, 2023, Trump Employee 4 informed Chief Judge [James E.] Boasberg that he no longer wished to be represented by Mr. Woodward and that, going forward, he wished to be represented by the First Assistant Federal Defender,” the filing states. It then details the repercussions: “Immediately after receiving new counsel, Trump Employee 4 retracted his prior false testimony and provided information that implicated Nauta, De Oliveira, and Trump in efforts to delete security camera footage, as set forth in the superseding indictment.”

That superseding indictment was produced a few weeks later.

This is not the first such incident, as you may recall. During the tenure of the House select committee investigating the Capitol riot, legislators unexpectedly announced a hearing centered on testimony from a former White House staffer named Cassidy Hutchinson. Hutchinson, too, had been receiving counsel from an attorney linked to Trump. Then, she wasn’t — and she suddenly provided investigators with much more evidence.

Her original attorney, Stefan Passantino, allegedly told Hutchinson that “the less you remember, the better” — though it is not clear for whom this was most directly beneficial. According to Hutchinson’s testimony, he suggested that she not try to reinforce her memory of what had occurred which, of course, would make it easier to accurately state that she didn’t recall those details.

When she offered testimony claiming not to remember details of one incident, she claimed that she fretted to Passantino about having committed perjury.

“They don’t know what you know, Cassidy,” she claims he told her. “They don’t know that you can recall some of these things. So you saying ‘I don’t recall’ is an entirely acceptable response to this.”

“They want there to be something,” he added, according to Hutchinson’s later testimony. “They don’t know that there is something. We’re not going to give them anything because this is not important.”

Hutchinson’s honesty with the committee, in other words, was less important than protecting that “something” — Trump’s alleged outburst in the back of a vehicle on Jan. 6 — from the committee’s awareness.

Hutchinson switched to an attorney outside of Trump’s sphere and offered more detailed testimony to the committee. Passantino later sued the committee for damaging his professional reputation.

For every $10 spent by Trump’s Save America PAC this year, $7 has gone to legal costs. Reports filed with the Federal Election Commission indicate that the PAC has spent north of $21 million on legal costs in 2023.

It’s not entirely clear how many people are represented by attorneys funded by Trump or his political action committee, but a Trump representative confirmed to The Washington Post in July that some staffers fell under that umbrella. This was framed paternalistically, as Trump seeking to “protect these innocent people from financial ruin and prevent their lives from being completely destroyed.”

There is one notable individual who isn’t fully enjoying that protection: Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani. The former New York mayor has reportedly been engaged in a fervent, months-long effort to have Trump recoup some of his own legal costs, an effort that’s included him and his attorneys appealing to Trump directly. According to the New York Times, this indifference to Giuliani’s costs is a cost-benefit analysis centered on Giuliani’s willingness to change his testimony.

“[P]eople close to both Mr. Trump and Mr. Giuliani take it as an article of faith that the former mayor would never cooperate with investigators in any meaningful way against the former president,” the Times’ Maggie Haberman and Ben Protess reported last week.

That said, Trump has reportedly agreed to help allay some of Giuliani’s costs. Confidence in Giuliani’s loyalty is one thing. But recent history shows that a little financial support offers its own legal rewards.